The Philosophy and Visual Arts of the Renaissance Indicate a New Interest in Power Sex God Humanity

Donatello, David, c. 1440, bronze, 158 cm (Museo Nazionale de Bargello, Florence; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

A life-size youth, naked except for a shepherd'southward hat and sandals, stands triumphant, ane human foot resting upon his foe's severed caput. The hand about his supporting leg holds a massive sword, while his other hand, placed at his hip, clasps a stone, presumably the one used to defeat the hulking warrior at his feet. This androgynous figure—cast in statuary by Donatello in the 1440s—is the adolescent King David, ancestor of Christ and hero of the Hebrew Bible. David famously defeated the giant Goliath, liberating his people armed but with a sling-shot and the grace of God. His story was a popular subject for renaissance artists. David's triumph of faith over brawn communicated anti-tyrannical political themes and epitomized the Christian bulletin that God's chosen people would inevitably prevail.

While the subject is Judeo-Christian, the form of this figure communicates a dissimilar ready of visual interests. Nowhere in the bible is David described as stripping down to his bare body to wage battle. David's sensual nudity and his contrapposto pose reflect the forms of ancient Greek and Roman infidel sculpture rather than those of the medieval era. The work is fully free-standing and, like an ancient sculpture, was originally displayed upon an elevated column. This placement, besides as the scale and bronze medium, are as well characteristic of aboriginal Greco-Roman art.

Donatello'southward David is an example of humanist interests crossing over into the realm of visual art: get-go in the thirteenth century, Italian buildings, sculptures, and paintings began to look increasingly like they did in the aboriginal Greco-Roman globe, even if the subject matter, contexts, and functions were vastly different. Eager to serve the interests of their classically inclined patrons and to demonstrate their own ingenuity, visual artists explored new approaches to class inspired by surviving art and architecture from antiquity too as ancient authors' discussions of them. (Come across this essay for a detailed word of humanism and its origins in literature.)

Detail of Domus Aurea, Rome, Italy (photo: sébastien amiet;l, CC BY 2.0)

What did they encounter?

Few ancient paintings survived for renaissance people to see. Excavations of Nero's Golden House in the 1480s did reveal fanciful paintings of animals, plants, people, architecture, and hybrids of these, which came to be called "grotesques". Even so, the main repositories of Roman painting known to united states of america, such as the extensive decorations at Pompeii, were non excavated until long after the renaissance and no painting from ancient Greece was known to have survived.

Athanadoros, Hagesandros, and Polydoros of Rhodes, Laocoön and his Sons, early beginning century C.E., marble, 7'ten 1/2″ high (Vatican Museums; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Archeological pursuits went manus-in-hand with humanist scholarship. Possibly the most famous example is the Laocoön, a 1st century C.Due east. marble sculpture described by the ancient writer Pliny as the greatest of all works of art. Excavated in 1506, the sculpture was discovered in the ruins of the palace of the Roman Emperor Titus—just where Pliny said it would be.

Raphael, drawing of the porch of the Pantheon in Rome, c. 1507–08, pen over stylus (Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle stampe, Uffizi)

Much of the ancient fine art known in the renaissance, however, was not excavated but already part of the visual environment: buildings and sculptures, mostly in a ruinous or fragmented state. Roman sarcophagi were used as tombs, fountains, and other forms of decoration. Massive structures like the Pantheon and Colosseum , numerous friezes and bronzes, triumphal arches , and scores of ancient coins had never ceased to be office of the Italian visual earth. Still, until the rising of humanism in the late medieval flow, involvement in these works was sporadic.

Left: Apollonios, Belvedere Torso, a re-create from the 1st century B.C.Due east. or C.E. of an before sculpture from the commencement half of the 2nd century B.C., marble, 159 cm (Museo Pio-Clementino, Vatican Museums; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); correct: Michelangelo, detail of Ignudo, ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, 1508–1512, fresco (The holy see, Rome)

The Belvedere Torso , for example, a fragmentary work from the 1st century B.C.Eastward., is the paradigm of an aboriginal sculpture that inspired renaissance artists such as Michelangelo, who adapted it for his famed ignudi on the Sistine Chapel ceiling. The work was likely unearthed for at least a century earlier anyone paid much attention to it. And, while Greco-Roman antiquity was revered, its material remains had not always been treated with reverence. Renaissance artists non only drew inspiration from ancient works, they also played an of import part in preserving it. Raphael famously pleaded with Pope Leo X to preserve ancient sites in Rome and protect them from pillaging.

Sandro Botticelli, Calumny of Apelles, 1494–95, tempera on console, 62 x 91 cm (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence)

Artists besides drew inspiration from written descriptions of art from antiquity. The detailed descriptions ( ekphrases ), of art by ancient authors like Pliny, Lucian, and Philostratus were influential on renaissance visual culture. Botticelli's Calumny of Apelles is perhaps the virtually famous example; the artist re-creates a work described past Lucian (whose text was widely translated in the fifteenth century) past the Greek artist, Apelles. In his 1435/six treatise On Painting , Leon Battista Alberti specifically singles out this ancient image—known merely through exact clarification—as a worthy source for artists and a model for narrative art.

Which Antiquity?

While information technology is helpful for a broad overview such equally this, to utilise a blanket term like "Antique" to designate cultural production of the aboriginal Greek and Roman worlds is misleading equally information technology suggests there was a unmarried artistic tradition, passed from Hellenic republic to Rome, that constituted art earlier the Christian era. In fact, what we designate as "ancient art" includes a vast range of subjects and styles. Renaissance artists responded to different facets of ancient fine art at different times, often due to their own or their patron'due south interests or to broader stylistic trends. Donatello, for case, drew upon Etruscan, Early Christian, Neo-Cranium, every bit well as ancient Greek and Roman art forms from diverse periods throughout his career.

Giorgione, Sleeping Venus, c. 1510, oil on panel, 108 x 175 cm (Gemäldegalerie, Dresden)

Scholars note that artists gravitated to those ancient fine art forms that best aligned with their personal or regional earth view. Venice, for instance, with its deep ties to the Byzantine visual tradition and nostalgia for terra firma , embraced the earth of romantic, erotic landscapes evoked by ancient pastoral verse and realized in works similar Giorgione's Sleeping Venus .

Leon Battista Alberti, Basilica of Sant'Andrea, 1472-90, Mantua (Italian republic) (photograph: Steven Zucker, CC: Past-NC-SA 3.0).

Old forms, new meaning

Greco-Roman art comprised a rich language of gestures and symbols to visually communicate to broad audiences, and information technology was adapted to new contexts. Architects designed buildings that re-used the vocabulary of ancient structures. Michelozzo's inventive designs for the Medici Palace in Florence (begun 1444) combine aboriginal and modern (medieval) forms in entirely novel ways. Topped with a massive overhanging cornice (classical), the structure's second and third stories display circular-biconvex (classical) and biforate windows (medieval), while the heavy rustication of the basis floor recalls the Palazzo dei Priori, Florence's (medieval) boondocks hall.

Christian spaces, like the church of Sant'Andrea in Mantua (begun 1470) designed by Alberti, creatively combines the form of an ancient triumphal arch—like the Curvation of Titus —with that of a temple front end—similar the Pantheon—while the flanking colossal Corinthian pilasters retrieve the ancient Roman arches of Septimius Severus and Constantine in the Roman Forum. These architectural forms are given new meaning past being re-used in a renaissance context. This hybrid of classical forms is ultimately new and not constitute in antiquity—these are old forms translated to new forms and given new meanings. At Sant'Andrea, the massive arch, a structure used to gloat armed forces triumph in aboriginal Rome, becomes a symbol of Christian triumph.

Brunelleschi, Crucifix, 1412–13, polychromed wood, 170 ten 170 cm, Santa Maria Novella, Florence (photograph: Steven Zucker, CC Past-NC-SA two.0)

Bodies, bodies everywhere

The idealized nude bodies of ancient figures, with their conscientious rendering of anatomical particular, appealed to renaissance Christians who understood humanity to exist created in the epitome of God . Brunelleschi's polychromed wooden crucifix in Santa Maria Novella shows Christ's life-sized body rendered with anatomical precision comparable to that of ancient sculptures, giving powerful physical presence to the Christian savior. This kind of palpable realism aligned with the new, urban religiosity of the early renaissance that promoted physically and emotionally charged piety. The reality of Christ's suffering torso would have encouraged sympathy and pity in worshipers. Anatomical specificity, like that demonstrated in Brunellschi's crucifix, reminded viewers of the reality of Christ's humanity only as it conjured the idealized beefcake of ancient art.

Orsanmichele, Florence, 1349 loggia (1380–1404 upper stories)

Lorenzo Ghiberti, Saint John the Baptist (replica), 1412–16, bronze, Orsanmichele, Florence (photo: Dan Philpott, CC BY two.0)

At Orsanmichele , a public grainery and shrine centrally located in Florence, the leading guilds of the city were tasked with providing big-scale sculptures of their patron saints to adorn the building'southward exterior. Conscious of the high visibility of this site, these powerful institutions sought to one-upward each other by commissioning the most avant-garde piece of work from the city'southward leading sculptors, including Nanni di Banco, Lorenzo Ghiberti, and Donatello. Cut edge hither meant sculpture all'antica , or "after the antique." Works were carved from marble or cast in bronze on a massive scale not common since the Roman era.

Ghiberti's Saint John the Baptist , standing a looming eight'4" was the first monumental bronze figure of the renaissance. Created for the guild of fabric finishers and merchants in foreign cloth, this plush bronze statue advertised the wealth of the sponsoring lodge. Ghiberti's saint also marks the development towards free-standing figural sculpture, a tradition popular in the ancient world simply largely unused in the medieval. While Saint John does occupy an architectural niche, the figure is rendered wholly in the round and stands within the space rather than being attached to the structure'south walls (meet the figures on the portal of Chartres Cathedral for an instance). This movement towards fully gratuitous-standing, or sculpture in-the-round, became a hallmark of the renaissance tradition, familiar to u.s. in the David sculptures of Donatello and Michelangelo .

Masaccio, Tribute Money, 1427, fresco (Brancacci Chapel, Santa Maria del Ruby, Florence) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA ii.0). The mural recounted an episode in the Gospel of Matthew in which Christ and his apostles pay a Roman tax collector.

Painted bodies

The new figurative manner embraced by sculptors like Ghiberti and Donatello was likewise adopted by artist'southward working in 2 dimensional media. In Masaccio'due south cycle of frescoes defended to the life of Saint Peter in Florence's Brancacci Chapel, the figures are modeled in calorie-free and shade to produce sculptural furnishings that advise their 3-dimensionality. In the scene of the Tribute Coin , the figures occupy a firm ground-line and their volumetric bodies cast regular shadows as though lit from a light source from the right. The figure types Masaccio develops for his apostles are relatable, rugged men of the street similar Donatello's Saint Marker at Orsanmichele and evoke the strong psychological presence found in images of Roman senators. Each figure is presented with a distinct human personality, responding to the unfolding scene through varied facial expressions.

Linear perspective diagram, Masaccio, Tribute Money, c.1427, fresco (Brancacci Chapel, Santa Maria del Ruby-red, Florence) (photograph: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0). Christ is the vanishing point.

Creating "real" infinite

The development of i-betoken linear perspective , a key invention of the early Italian renaissance, was as well informed by humanism. Brunelleschi, the famed architect of the Florentine Duomo , is credited with devising this system, inspired by his careful study of ancient Roman monuments and medieval Arabic and Latin theories of optics. Brunelleschi's theories were codification by Alberti in his treatise on painting, which gave detailed instructions for constructing mathematically defined space then that painters may create the appearance of iii dimensions in their art. To requite credibility to this type of contrived spatial construction, Alberti draws upon the writing of the aboriginal author Vitruvius whose widely read 1st century B.C.East. treatise, On Architecture , celebrated the illusionistic mathematical space of aboriginal Roman painting.

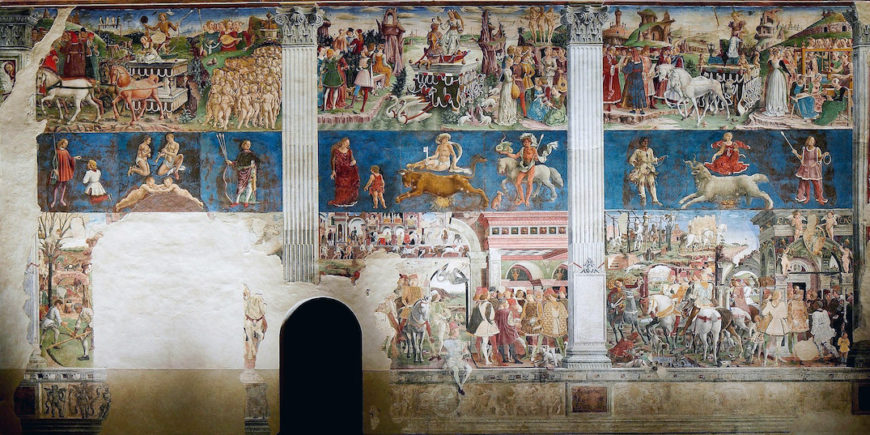

Francesco del Cossa, Cosme Tura, and Ercole de' Roberti, frescoes of March, April, and May, 1469–70, Salone dei Mesi, Palazzo Schifanoia, Ferrara, Italy (public domain)

New/Erstwhile subjects

One of the critical developments of the fifteenth century was the transformation of the subjects of aboriginal mythology into large-scale imagery. Previously used primarily for religious subjects, renaissance artists employed the awe-inspiring scale for the gods and heroes of antiquity.

In the Hall of the Months at the Palazzo Schifanoia in Ferrara, the artists Francesco del Cossa, Cosme Tura, and Ercole de' Roberti frescoed the walls of Duke Borso d' Este's pleasure palace with large-scale scenes that combined images of contemporary court life with heathen subjects. Divided into twelve sections, each set of images is separated by Corinthian columns, and includes at the everyman register a scene from Borso's court—such as the knuckles dispensing justice or interacting with courtiers—above which is the zodiac sign for the calendar month depicted and, at the highest annals, a triumphal depiction of the pagan god associated with that month.

Francesco del Cossa, Cosme Tura, and Ercole de' Roberti, detail of Duke Borso and court, 1469–70, Salone dei Mesi, Palazzo Schifanoia, Ferrara, Italian republic (photo: Sailko, CC BY-SA iii.0)

Throughout the imagery at Schifanoia are recognizable portrait likenesses of Duke Borso. While incorporated into a larger narrative, these likenesses do point to another primal humanist-inspired development of the early renaissance: the genre of independent portraiture.

Living sinners depicted in art

While popular in aboriginal Greece and Rome, portraiture had all simply disappeared in European art until the fifteenth century. The many surviving portrait busts of Roman senators and the heads of emperors on imperial coins fascinated renaissance audiences and provided gear up models for the rise genre. Initially used to record the features of the ruling class, portraiture spread in popularity and became a key form of celebration for the rise merchant and artisan classes.

Left: Pisanello, Leonello d'Este, 1441, tempera on panel, 28 x 19 cm (Accademia Carrara); center: Pisanello, medal of Leonello d'Este, c. 1441–44 (possibly cast 16th century), yellowish copper alloy with nighttime brown patin. vi.five cm bore (The Metropolitan Museum of Art); correct: sesterius of Trajan, 103–111, statuary, 3.4 ten .iv cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

An early case is Pisanello's portraits of Leonello d'Este which show the Ferrarese ruler in contour and bosom-length, an arroyo drawn from the tradition of purple profile portraits on ancient coinage. By the belatedly fifteenth century the profile view was largely displaced by the iii-quarter view (initially popular in northern Europe), seen in Botticelli'due south Portrait of a Homo with a Medal of Cosimo de'Medici . Turning the sitter towards the viewer encouraged a new kind of viewing experience, one that suggested a reciprocity with the audition—the viewer looks upon the sitter who appears to look back.

Humanism and the rising status of the artist

Humanist interests informed another key development of the renaissance: the rising social status of the visual creative person. The authors of antiquity celebrated the creations of their own leading artists and described the honors paid to them, giving renaissance patrons reason to encourage creative ingenuity and artists worthy models to emulate. Traditionally seen as apprehensive craftsmen and valued as manual workers (still skilful), visual artists became increasingly appreciated for their intellectual abilities during the early renaissance. Artists commanded ever greater social prestige so that by the sixteenth century it meant something to own a piece of work past Raphael, Michelangelo, or Mantenga. Works of fine art were seen as expressions of individual ingenuity, valued for the virtues attributed to their creators.

Renaissance Italy and beyond

Humanism and its reflection in contemporaneous fine art was certainly non confined to the Italian globe. Artists north of the Alps and beyond Europe likewise responded to the forms of ancient art, but every bit in the Italian peninsula, they did so in means that reflected their personal and regional interests. There is no single renaissance style inspired by the "Antique" anymore than there was a single antiquarian globe. Much the same tin be said for our own, modernistic-day artistic engagements with the Greek and Roman past. The whitewashed world of the 1959 film Ben Hur or the heavily muscled hunks of the 2006 epic 300 say much more virtually us than they practise the aboriginal past. Such was always the case.

Additional resource:

Leonard Barkan, The Gods Made Mankind: Metamorphosis and the Pursuit of Paganism (New Oasis, Yale UP, 1990).

Leonard Barkan, Unearthing the By: Archæology and Aesthetics in the Making of Renaissance Culture (New Haven: Yale Upwardly, 1999).

Phyllis Pray Bober and Ruth Rubinstein, Renaissance Artists and Antique Sculpture: A Handbook of Sources , second revised edition (London: Harvey Miller Publishers, 2010).

Patrick Baker, Italian Renaissance Humanism in the Mirror (Cambridge: Cambridge Up, 2015).

Malcolm Bull, The Mirror of the Gods: How Renaissance Artists Rediscovered Pagan Gods (London: Oxford UP, 2005).

Stephen J. Campbell, The Chiffonier of Eros: Renaissance Mythological Painting and the Studiolo of Isabella d'Este (New Haven: Yale UP, 2004).

Rebekah Compton, Venus and the Portrayal of Dearest in Renaissance Florence (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2021).

Charles Dempsey, The Portrayal of Love: Botticelli'southward Primavera and Humanist Civilisation at the Fourth dimension of Lorenzo the Magnificent (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Upward: 1992).

Luba Freedman, The Revival of the Olympian Gods in Renaissance Art (Cambridge: Cambridge Upwardly, 2003).

Luba Freedman, Classical Myths in Italian Renaissance Painting (Cambridge: Cambridge Upwardly, 2011).

Kristen Lippincott, The Frescoes of the Salone dei Mesi in the Palazzo Schifanoia in Ferrara: Style, Iconography and Cultural Context . Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Chicago, 1987.

Sarah Blake McHam, "Donatello's Bronze "David" and "Judith" as Metaphors of Medici Rule in Florence," The Art Message 83, no. i (2001), pp. 32-47.

Jean Seznec, The Survival of the Pagan Gods: The Mythological Tradition and Its Place in Renaissance Humanism and Art (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Upwardly, 1972)

Robert Weiss, The Renaissance Discovery of Classical Antiquity (London: Oxford UP, 1988)

Source: https://smarthistory.org/humanism-italian-renaissance-art/

0 Response to "The Philosophy and Visual Arts of the Renaissance Indicate a New Interest in Power Sex God Humanity"

Post a Comment